What's in a Sequel: Bioshock and Bioshock 2

Sequels are crazy common in the video game world. Maybe it’s because the developers feel more comfortable with an established IP (intellectual property), maybe it’s because the money people push for something with more brand recognition, or maybe developers just think they have some more stories left to tell. Any way you slice it, Space Marine Shooter will sure as hell spawn Space Marine Shooter 2, as long as Space Marine 1 sells well enough. Let’s have a look at a notable game and its sequel and see what went right, what went wrong, and why. For this edition, let’s have a look at Bioshock and Bioshock 2.

To start, we need to know what makes a good sequel. It’s hard to establish a hard and fast rule, but I’ll say that a good sequel needs to expand upon the ideas of the original while exploring new territory.

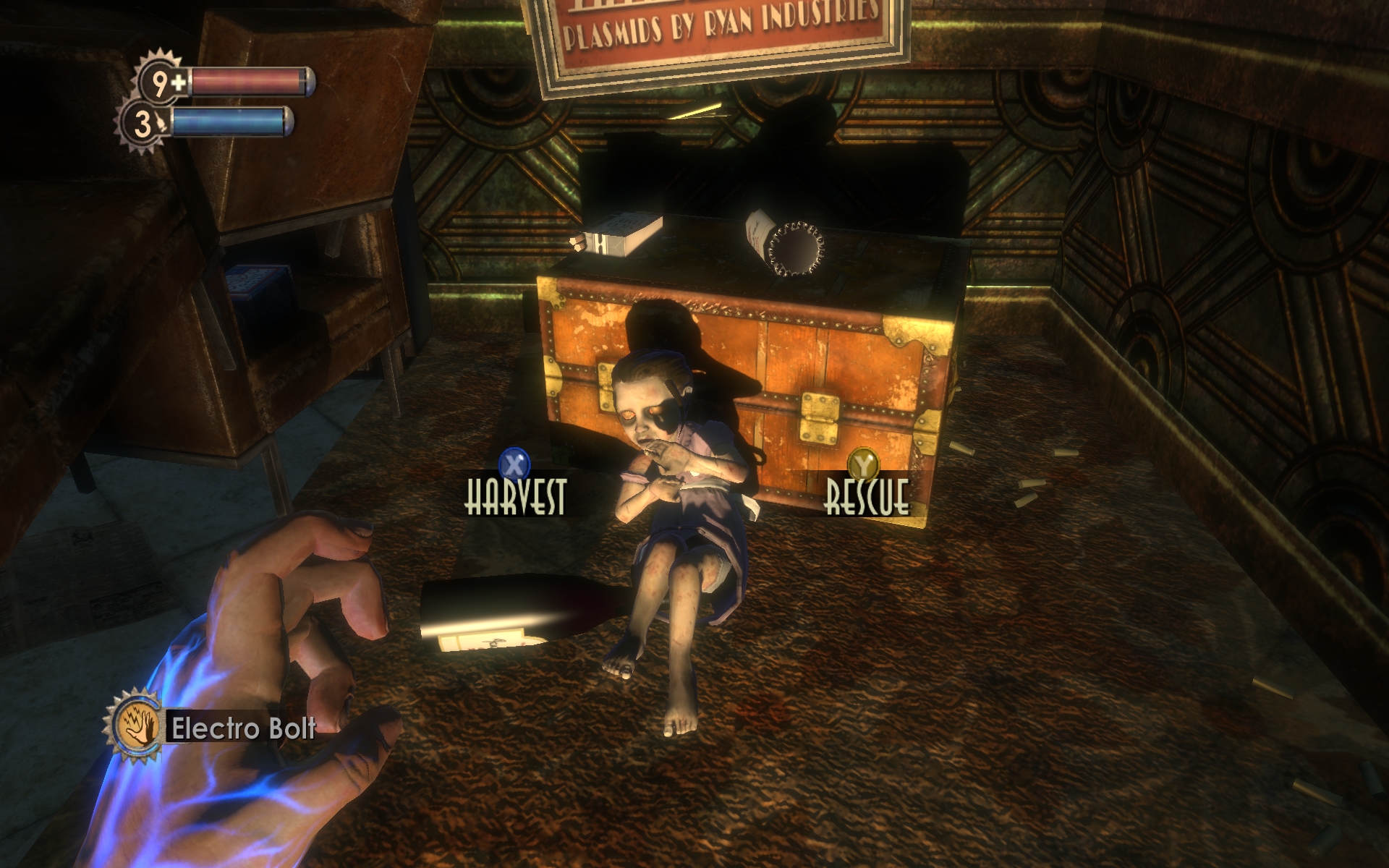

Bioshock was renowned for its story. It’s a tale of Objectivism gone mad. Andrew Ryan, an Ayn Rand stand in, creates a utopia underwater for society’s elite, named Rapture. After a few successful years, a scientist named Brigid Tenenbaum discovers Adam, a genetic wonderdrug that lets anybody rewrite their DNA to give themselves fantastic abilities. Society quickly falls apart when addiction sets in and the crème of society’s crop start killing each other for a fix. Twisted human beings roam the city, and the Scuba suit enclosed Big Daddies protect the grotesque Little Sisters as they gather Adam from corpses. You enter years later, a victim of a freak plane crash in the middle of the Atlantic. Bioshock tells you one simple thing: You make choices but, in the end, your choices make you.

Bioshock 2 did not get the praise that the original did, especially not for its story. You play as a prototype Big Daddy who has his Little Sister reclaimed by her biological mother. Sophia Lamb, the girl’s mother, forces you to shoot yourself in the head, but you somehow survive. 10 years later you wake up, revived by Little Sisters under control of your former Little Sister Eleanor. Her mother activates a prototype failsafe designed to keep the Big Daddies from wandering away from their Little Sisters. Your heart will slowly stop working if you cannot make contact with Eleanor. Throughout the game, Eleanor attempts to help you while her mother attempts to kill you. Where Andrew Ryan spoke about the power of the self, the “Great Chain of Progress”, and free enterprise, Lamb speaks about the power of “The Rapture Family”, faith, and altruism.

While Bioshock 2 certainly added a new angle for its story, it still boils down to the same general thing as Bioshock, with a very important exception that I’ll get into in a bit. In both games you are still opposed by a person with control of Rapture’s citizens, including the Big Daddies and Little Sisters. In both games, you can rescue or harvest the Little Sisters, but it falls flat. There's no middle ground between being a saint and being the devil, and in both games, you are rewarded more for taking the moral path. The problem with this is that for the whole game, you're told that taking the high ground means you're making sacrifices. There are more moral choices to make in Bioshock 2 besides just “will you harvest the little sisters or rescue them”, which is interesting, but it doesn’t really lead anywhere. You encounter several people who have wronged you or Eleanor and you can choose to kill them or spare their lives, which changes the ending a bit. Bioshock’s Andrew Ryan makes for a much more compelling antagonist than Sophia Lamb. Lamb comes off as dry, and a bit uninspired where Ryan came off as furious, charismatic, and dangerous. While both characters speak to you continuously throughout the game, Lamb is much more accessible and when you do finally confront her, there’s not nearly as much nuance and emotional buildup as there is with Ryan. Bioshock 2 feels like it should have been an expansion, rather than a standalone game. There is one area where Bioshock 2 trounces Bioshock though: Motivation. In Bioshock 2 you have a clear and extremely pressing motivation to move forward. Your heart is stopping and only being with Eleanor can save your life. In Bioshock, you’re just dropped into Rapture and expected to move forward because some Irish guy named Atlas says, “Would you kindly?” It feels like there should be a moment when you at least try to escape from the city. Near the end of the game, there is a justification for this, but it feels very hollow until then, and makes the whole deal a little less plausible.

Bioshock also got a lot of praise for its combat system, which relies on both guns and “plasmids.” Plasmids are essentially magic and you have access to the usual lot (fire, lightning, telekinesis, etc.), but there are a few interesting ones, like the ability to temporarily trick Big Daddies into protecting you, or the ability to create a temporary hologram that enemies will chase. There is also a whole slew of “Gene Tonics” which give you passive boosts like increased speed, or an easier time hacking the various machines around Rapture. You can even hack stationary turrets and security drones so that they protect you, which is fun. Maybe ironically, the combat is at its best in the beginning of the game when you are forced to use your environment to defeat the heavily armored and equipped Big Daddies. You hack the turrets, security cameras, and security drones to create a hail of lead that allows you to take down even the strongest enemies. Constraints breed creativity and all that. As the game progresses, you become so strong that you take down multiples big daddies with ease, which takes a lot of the fun out of the combat.

Bioshock 2 on the other hand, made combat faster, punchier, and deadlier. Your weapons are souped-up versions of Bioshock’s, but they are tailored to your larger stature and are fittingly more destructive. Your plasmids have also been expanded, with a few new abilities. Your hacking ability has also been improved, with the ability to heal and improve your hacked drones, turrets, and cameras. While you’ve definitely lost the fun of setting up traps and such for larger enemies, combat has become much more enjoyable overall. There are more gene tonics with verifying effects that really allow you to change up your playstyle, more than just moving faster or doing more damage with your melee weapon, like in the previous game.

While similar, Bioshock 2 has far superior combat in almost every way. Bioshock’s combat can feel a little plodding and wooden, and the later stages of combat feel far too easy. Bioshock 2 has difficult combat throughout, along with a number of different playstyles, rather than just the running and gunning of Bioshock. However, Bioshock has the advantage when it comes to traps. There’s something so fun about setting up a corridor littered in proximity mines, turrets, and hacked sentry drones. You fire off a shot at the Big Daddy and gleefully watch him come careening through your carefully designed snare, or panic as it all goes wrong at the last second somehow. Bioshock 2 also wastes the opportunity to really change up how combat works by not focusing enough on the fact that you are a Big Daddy. It’s pretty well established that Big Daddies are slow, heavily armored, and extremely deadly. While you’ve got the deadly bit down pat, you’re as damageable as you were in the first game, and you are far too fast. It would have been really interesting if the game forced you to play at a slower pace, rather than taking the safe route of giving players exactly what they had in the last game.

So, now we come to the real question. How did Bioshock 2 do as a sequel?

Unfortunately, not so well. While Bioshock 2 did have better combat and an arguably better story motivation, it re-used so much from Bioshock from the general story arc, to the array of the weapons, to the game feel without really trying anything new. If you play Bioshock and skip 2, you wouldn’t be missing much besides the improved combat. While playing as a Big Daddy is fun, bigger doesn’t always equal better.