Scale, Size, and Scope: The Mass Effect Series

After a successful game, it always seems that the game designers ask themselves the question: “how do we make it bigger?” As a result, often the sequel ends up jumping the shark – so named for the Happy Days episode where somebody literally jumped over a shark. In other words, the plot nosedived from epic to ridiculous faster than the main character could clear the dorsal fin. Gaming has generally been the second home for the bombastic action sequence after movies of course, so game designers should really consider this question instead: “how epic is too epic?” The Mass Effect Series had a really good approach to scale and scope.

So, what makes the Mass Effect Series idea of scale different?

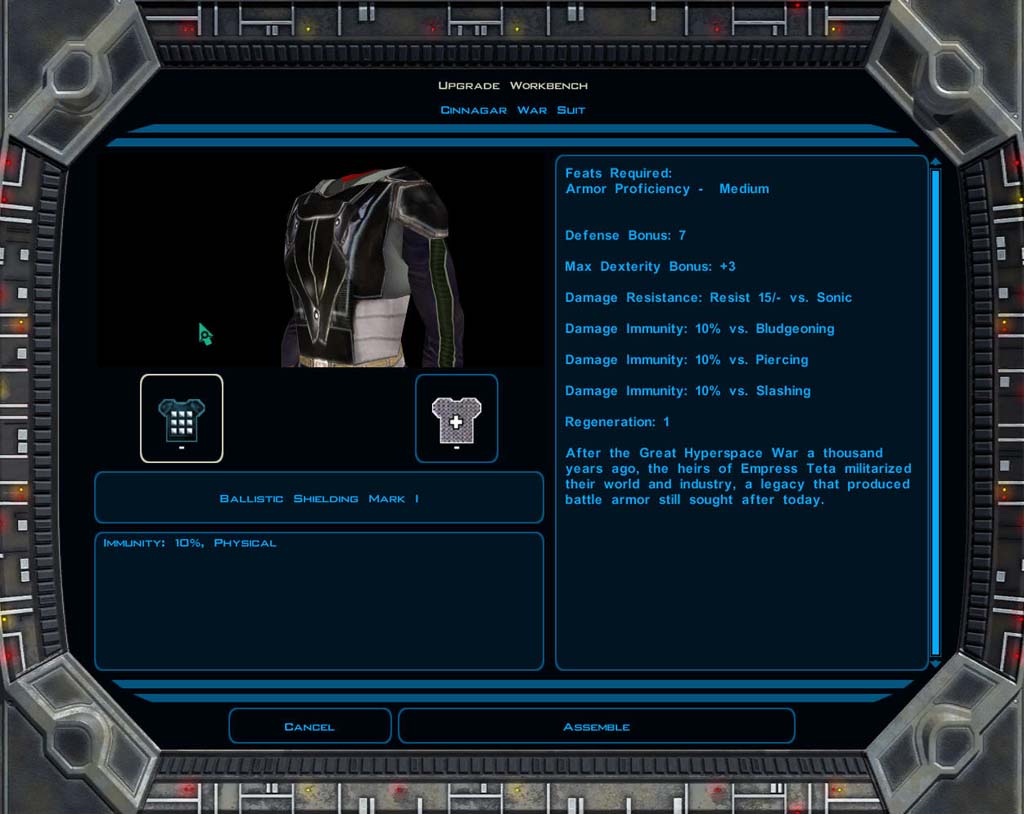

Mass Effect, the first game in the series, feels small scale, despite the galaxy-wide implications of your mission. The story starts out with Geth, the reclusive race of machines, attacking a human colony. You, Commander Shepard, expose Saren and his involvement with the Geth, and track him down for the rest of the game. The pacing of Mass Effect makes you feel as if you’re just on Saren’s tail the whole time because you just miss him, or clash with him every time. Since you spend most of your time in a self-contained ship with a clear-cut mission ahead of you, the large number of planets you visit fade into the background. Rather, the story is really about Shepard, and how you choose to develop them as a character.

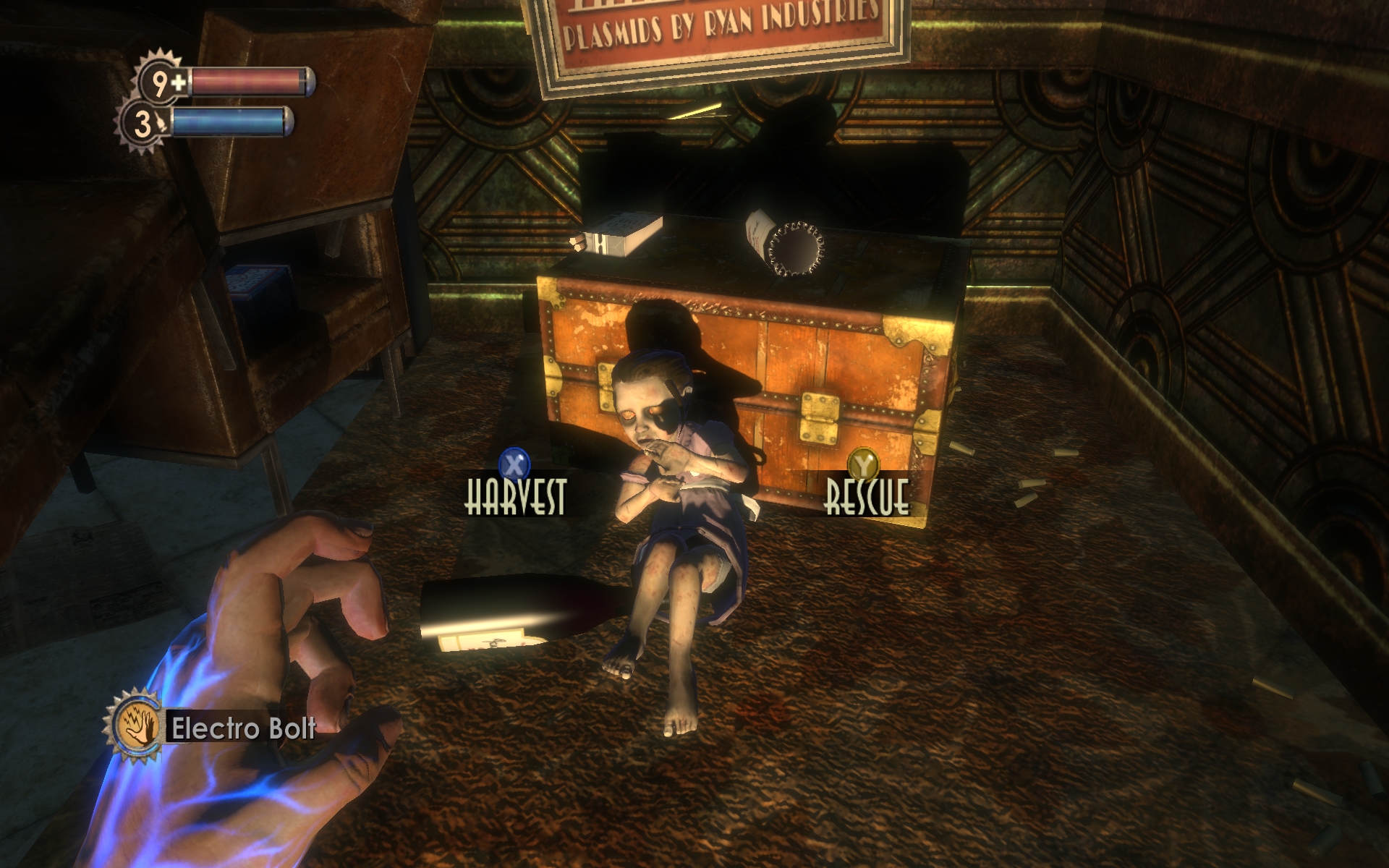

In Mass Effect 2 instead of dealing with an entire army, you are trying to stop a single ship. A huge ship kills off Shepard and destroys your ship in the first five minutes, which is a hell of a memorable start to any adventure. Cerberus, a pro-human terrorist group, brings you back to life to you chase after the Collectors who are abducting human colonists. Turns out, they’re all on the same ship that killed you at the beginning of the game. The Collectors are presented as mysterious, yet one-dimensional, so you spend most of your time building your team. Each member is detailed, has a unique backstory and loyalty mission, and is generally enjoyable to talk to. In fact, most memorable moments of the game don’t revolve around you, but your teammates.

Mass Effect 3 is the appropriately grandiose last hurrah. Within the first ten minutes of starting up the game, you escape Earth as The Reapers annihilate Earth’s armies. You acquire companions, but as The Reapers, as ominous as The Collectors were bland, threaten the entire galaxy, your mission doesn’t focus on your team, but on helping the galaxy prepare for what might be their last stand. Shepard, by this point, practically legend, doesn’t have much character exploration left. Much of the cast from ME1 and ME2 return, though your squad is much smaller. With these familiar faces, you focus more on the places you go and the people around you. It’s a clever subversion of the intense character-introspection of earlier games, but it’s almost expected; this is the final game in an epic trilogy, of course it would be about the spectacle. Yet, it never feels like too much, overblown, and manufactured.

Ending a trilogy like Mass Effect is like difficult, and many might say that it was underwhelming, but I’m not sure if there was a better way to tie everything up. Once you dig into each game, you can see how the designers used scale to make you care about Shepard, your companions, and then the galaxy. Because you care about all three of these aspects of the game, the conclusion feels like the end of a cohesive journey.